You know the sinking feeling when a production line stops. You hear the press crunch, see the fractured metal, and watch your scrap rate climb. You check the tooling, but deep down, you suspect the raw material is the real culprit. In the high-speed world of two-piece can 1 manufacturing, choosing the wrong steel substrate isn’t just a mistake; it is a profit killer.

Yes, Electrolytic Tin Plate (ETP) is highly suitable for Draw-Redraw (DRD) processes, provided you select the correct base steel temper and grade. ETP offers superior natural lubricity compared to other coatings, which reduces galling on tooling, and its excellent ductility supports the multi-stage forming required for food cans without fracturing.

Many of my clients ask me if they should switch to Tin-Free Steel 2 (TFS) to save money, or if ETP is still the king of the hill. While TFS has its place, ETP brings a unique set of mechanical advantages that make it indispensable for specific deep-drawing applications. Let’s dig into the technical details so you can make the right buy for your next order.

Which temper is soft enough for deep drawing 2-piece cans?

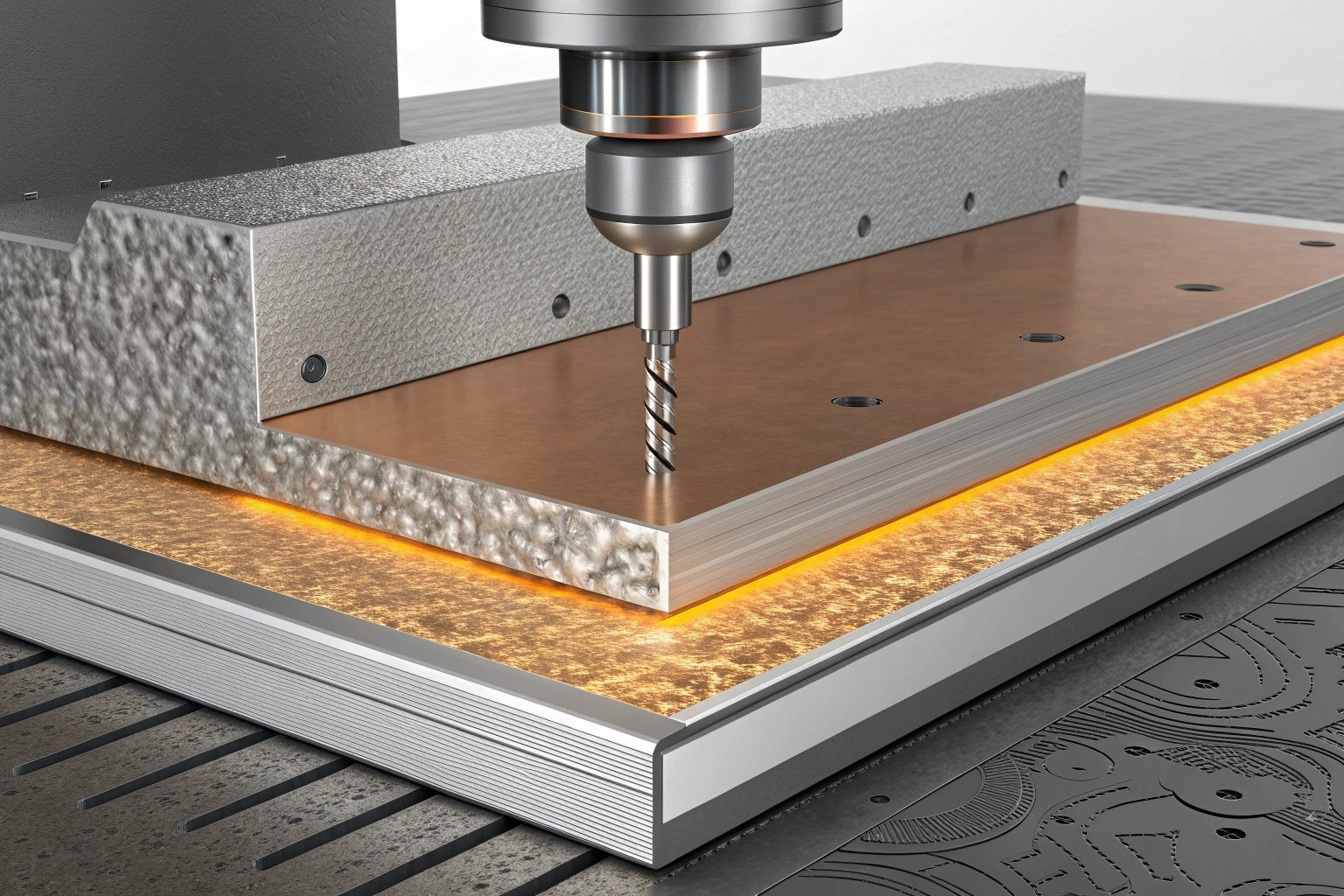

When you force a flat sheet of steel into a cup shape, you are asking the metal to do something unnatural. If the material is too hard, it snaps. If it is too soft, it might not hold the structural integrity needed for the final can. I have seen production managers pull their hair out because they ordered a "standard" temper that simply couldn’t handle the draw ratio of their new mold.

For deep drawing applications, you typically need a softer temper, such as T-1 (Type A) through T-3 (Type C), or specific Deep Drawing (DD) grades which prioritize elongation. However, for modern DRD cans where wall strength is vital, Double Reduced (DR) grades like DR8 are often used, but they require precise control over the anisotropy and grain structure to prevent cracking.

Understanding the Balance of Strength and Ductility

The choice of temper is arguably the most critical decision you will make when ordering Electrolytic Tin Plate (ETP) for Draw-Redraw (DRD) cans. In my experience dealing with global buyers, there is often a misconception that "softer is always better" for drawing. While softness (high elongation) helps prevent fractures during the initial draw, the final can needs to be strong enough to withstand retorting (cooking) pressures and stacking weight.

If we look at the metallurgy, we are balancing two opposing forces: Yield Strength 3 and Elongation.

For a shallow draw, a harder temper (like T-4 or T-5) might work and allows you to use thinner steel, saving money. But for a DRD process, where the metal is drawn, and then drawn again to increase the height and reduce the diameter, the stress on the crystal lattice of the steel is immense. If the temper is too hard, the material reaches its failure point before the shape is fully formed. Conversely, if we use a material that is too soft, we might see "wrinkling" on the sidewalls or the bottom of the can might dome outwards under pressure.

Here is a breakdown of how we typically categorize tempers for these applications:

Table 1: Common Tempers for DRD Applications

| Temper Code | Hardness (HR30T) | Characteristics | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-1 (Type A) | 49 ± 3 | Extremely soft, high ductility. | Deep drawn parts with complex shapes, nozzles. |

| T-2 (Type B) | 53 ± 3 | Moderate softness. | Moderate draws, rings, and closures. |

| T-3 (Type C) | 57 ± 3 | General purpose, medium stiffness. | Shallow drawn cans, can bodies. |

| DR-8 | 73 ± 3 | Double Reduced, stiff but strong. | High-strength DRD cans (requires precise tooling). |

| DR-9 | 76 ± 3 | Very stiff. | Mostly used for can ends, rarely for deep bodies. |

When I work with clients like you, I always ask for the Draw Ratio (the ratio of the cup height to the diameter). If your draw ratio is high, we simply cannot use standard Double Reduced (DR) material without risking fractures. We might need to look at a Batch Annealed 4 (BA) product which tends to have a more forgiving grain structure than Continuously Annealed (CA) steel.

Furthermore, we must consider the directionality of the steel properties. In DR grades, the rolling direction creates a "grain" similar to wood. The steel will stretch differently along the grain versus across it. If you use a high-temper DR grade for a deep cup, you might find the cup splits along the rolling direction. This is why for the deepest draws, we often revert to single-reduced, softer tempers, even if it means using a slightly thicker gauge to maintain can strength. It is a trade-off, but one that ensures your production line keeps running without jamming.

How do I prevent "earing" on the top edge of the drawn can?

I recall a project where a customer in Italy was producing tuna cans. They were furious because every time they trimmed the cans, they generated 5% more scrap than budgeted. The tops of their cans looked like wavy potato chips before trimming. This phenomenon, known as "earing," is a silent budget killer. It forces you to trim more metal off the top to get a flat edge, which means you are buying steel just to throw it in the scrap bin.

To prevent excessive earing, you must control the planar anisotropy of the steel sheet, which is dictated by the rolling and annealing process at the mill. While you cannot eliminate earing entirely, you can minimize it by specifying "non-earing" or "low-earing" quality steel, where the manufacturer ensures the difference in mechanical properties across different directions (r-value) is minimized.

The Economics and Physics of Earing

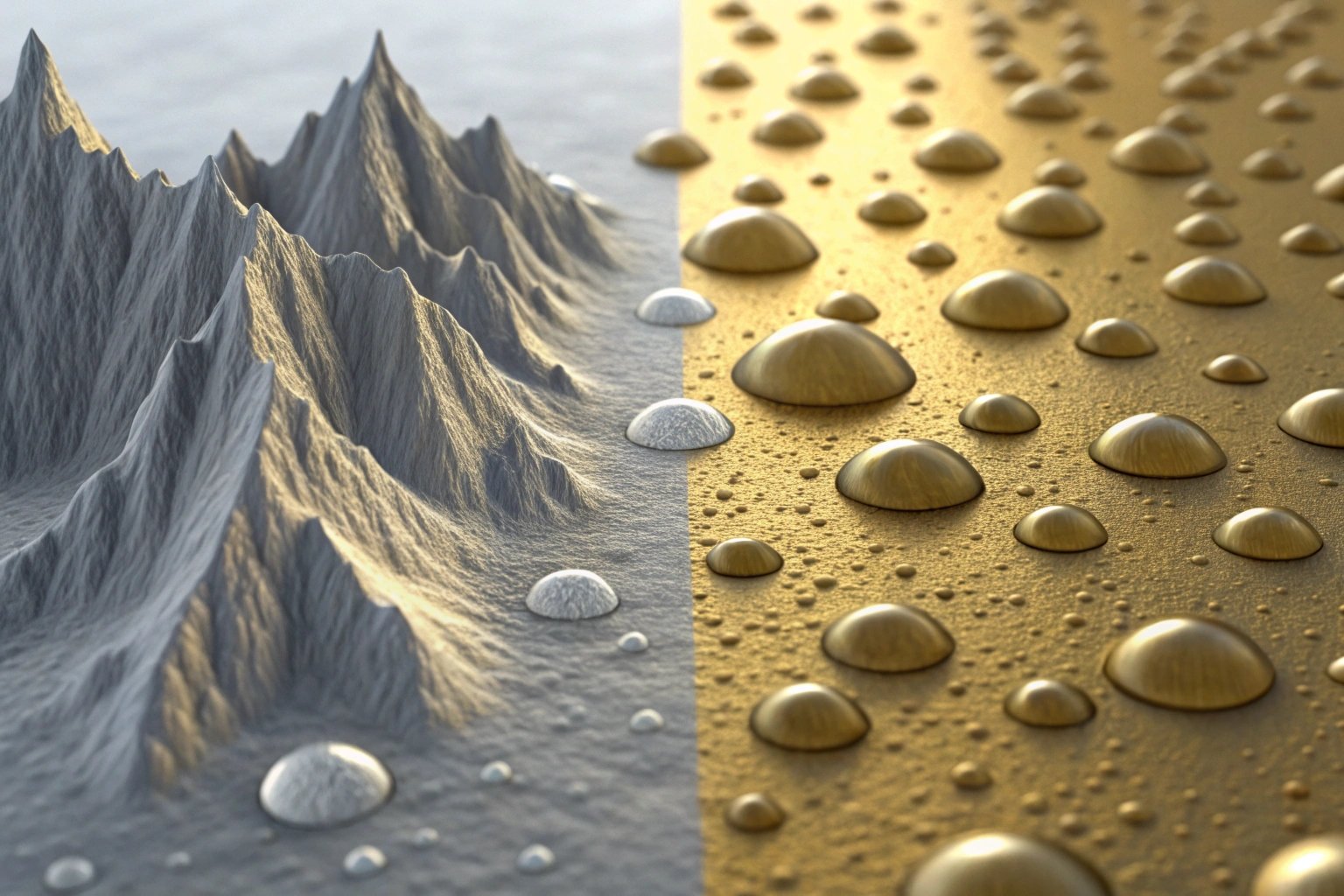

Earing is not just a cosmetic issue; it is a direct reflection of the steel’s internal crystal structure. When steel is rolled into thin sheets at the mill, the crystals elongate and align in the direction of the rolling. This creates Anisotropy 5—meaning the material is stronger or stretchier in one direction than another.

When your press punches down to draw a round cup from this sheet, the metal flows easily in some directions (usually 45 degrees to the rolling direction) and resists flowing in others (usually 0 and 90 degrees). The result? The rim of the cup is not flat. It has "ears" or peaks where the metal didn’t flow, and valleys where it did.

Why does this matter to your bottom line? Imagine you want a finished can height of 40mm.

- With Low Earing: You might be able to draw the cup to 42mm and trim off 2mm to get a flat edge.

- With High Earing: The "valleys" might dip down so low that you have to draw the cup to 45mm just to ensure the lowest point meets your 40mm requirement. You then have to trim off 5mm of "peaks."

That extra 3mm of steel per can adds up to tons of wasted material over a year.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common DRD Defects

| Defect Type | Visual Symptom | Probable Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earing | Wavy, uneven top edge. | High planar anisotropy (r-value variation). | Switch to "Non-earing" grade; Adjust blank holder pressure. |

| Fracturing | Cracks at the base or wall. | Material too hard (low n-value); Insufficient lubrication. | Use softer temper; Check tin coating weight; Inspect die radius. |

| Wrinkling | Ripples on the flange/wall. | Low blank holder force; Material too thin/soft. | Increase holder pressure; Use slightly harder temper. |

To solve this, we focus on the Delta r-value ($\Delta r$). This value measures the variation in plastic strain ratio 6 in different directions. Ideally, we want $\Delta r$ to be zero. In reality, it never is. However, we can control it.

When you order from us, if you specify "DRD Quality" or "Low Earing," we adjust the cold rolling reduction rates and the annealing temperature. Batch Annealing (BA) typically produces steel with higher anisotropy (more earing) compared to Continuous Annealing (CA), although BA is softer. This is a tricky conflict: you often want soft steel (BA) for the draw, but you want consistent steel (CA) to stop the earing.

This is why we often recommend aluminum-killed, continuously annealed steel for difficult DRD applications. It offers a "sweet spot"—it is clean enough to stretch but processed in a way that keeps the crystals more randomly oriented, smoothing out those waves at the top of your can.

Do you have a non-earing quality tinplate for DRD cans?

It is the question every savvy buyer asks eventually. You want the perfect material—one that acts like a liquid and flows evenly into the mold without any waste. I always appreciate this question because it shows the buyer understands the manufacturing process. However, I also have to be the honest voice in the room: in the world of metallurgy, "perfect" does not exist, but "optimized" certainly does.

We supply "low-earing" quality tinplate specifically designed for DRD cans, achieved by strictly controlling the cold-rolling reduction ratio and annealing temperatures to balance the r-values. While a strictly "zero-earing" material is scientifically impossible in mass-produced steel, our high-grade DRD stock keeps earing within tight tolerances to minimize trim waste.

Defining "Non-Earing" in the Real World

When we talk about "non-earing" quality, we are technically using a marketing term for Isotropic Steel. In a perfect world, an isotropic material has identical properties in all directions (X, Y, and Z axes). But steel is crystalline. It has a lattice structure. When we roll it, we squash that lattice.

To get close to a "non-earing" quality, we have to look at the n-value 7 (work hardening exponent) and the r-value (plastic strain ratio).

- High r-value: Means the material resists thinning. This is good because we want the walls to stay thick and strong.

- Uniform r-value: Means the material flows the same way in all directions.

For our DRD customers, we use specific processing routes. For example, we might control the finish rolling temperature and the coiling temperature at the hot rolling stage, long before it even becomes tinplate. If the hot-rolled coil has a coarse grain structure, no amount of cold rolling will fix the earing later.

We also strictly manage the "skin pass" or temper rolling. This is the final light roll that gives the steel its surface finish and final mechanical properties. By adjusting the tension during this phase, we can slightly correct the grain orientation.

The Role of Chemistry

It is not just about physical rolling; it is about chemistry. Carbon content plays a role. Ultra-low carbon steels (Interstitial Free 8 or IF steels) have amazing deep drawing properties and very low earing, but they are expensive and often too soft for can bodies that need vacuum resistance. We typically use a clean, low-carbon steel chemistry (Carbon < 0.06%) for DRD applications. This provides the best compromise between cost, strength, and flow.

When you request "Non-Earing" quality, what you should actually ask for is a specification on the earing percentage. For example, "Earing must not exceed 2% of the cup height." This gives us a clear target. If you just ask for "non-earing," some suppliers might send you standard stock and hope for the best. By defining the tolerance, you force the supplier to select coils from the middle of the production run where consistency is highest, avoiding the "head and tail" of the coil where temperature variations can cause inconsistent crystal growth.

Is the coating flexible enough to not crack during the draw?

I have seen it happen: a beautiful looking can comes off the line, but a week later, it’s rusting from the inside out. The steel didn’t fail; the coating did. In a DRD process, the surface of the metal is stretching significantly. If the protective tin layer or the passivation film cannot stretch with the steel, micro-cracks form. These cracks are open doors for acid from the food to attack the steel base.

The tin coating on Electrolytic Tin Plate (ETP) is exceptionally flexible and acts as a solid lubricant, allowing it to stretch with the steel base without cracking during the draw. However, the success of the coating depends on the "finish" selected; a Matte (unmelted) finish is often preferred for severe draws as it retains lubrication oil better than a bright, flow-melted surface.

The Lubricity Factor: Tin’s Secret Weapon

This is where ETP truly beats other materials like Tin-Free Steel (TFS/ECCS). Tin is a soft, malleable metal. When you subject it to the high pressure of a draw-redraw press, the tin actually flows. It acts as a solid-state lubricant between the steel sheet and your carbide dies.

In the industry, we call this preventing Galling 9. Galling is when the steel sheet gets hot and momentarily welds itself to the tool, ripping the surface. Because tin melts at a low temperature and is naturally soft, it prevents this steel-on-steel contact. This extends the life of your expensive tooling and ensures the can wall remains smooth.

Surface Finish: Bright vs. Matte

You might think a shiny, bright can looks better, so you should order "Bright" or "Flow Melted" tinplate. For DRD, this is often a mistake.

- Bright Finish: The tin has been melted and reflowed. It creates a dense, alloyed layer. It is smooth and shiny.

- Matte (Stone) Finish: The tin is deposited but not reflowed. It has a rougher, micro-textured surface.

For deep drawing, Matte is superior. Why? Because those microscopic peaks and valleys on the surface hold oil/wax. When the punch hits the metal, that trapped oil is released under pressure, providing critical lubrication exactly when it is needed. A bright, smooth surface squeezes the oil away too quickly, leading to friction and scratches.

Table 3: Coating Comparison for DRD

| Feature | Electrolytic Tin Plate (ETP) | Tin-Free Steel (TFS/ECCS) |

|---|---|---|

| Lubricity | High. Tin acts as a natural lubricant. | Low. Hard chrome coating is abrasive on tools. |

| Coating Flexibility | Excellent. Tin stretches with the steel. | Fair. Chrome layer can micro-crack in deep draws. |

| Weldability | Yes. Can be welded if needed. | No. Cannot be welded (must be glued/bonded). |

| Corrosion Resistance | Good. Sacrificial protection for steel. | Excellent. Superior adhesion for lacquers. |

| Tool Wear | Low. Soft tin protects dies. | High. Hard chrome wears dies faster. |

The Lacquer Variable

Finally, we must discuss the lacquer. In many DRD applications, you are pre-coating the flat sheet before drawing (Pre-coated coil). The tin layer will survive the draw, but will the lacquer?

This is the main limitation of ETP compared to TFS. Because tin melts at roughly 232°C (450°F), you cannot bake the lacquer at high temperatures, or the tin will reflow and ruin the appearance (a defect called "wood graining"). You must use lacquers that cure at lower temperatures. If your process requires a high-temperature cure for food safety reasons, we might have to discuss specialized Passivation 10 treatments or look at alternative coating technologies. But for the metal itself, the tin layer is incredibly resilient and will follow the steel wherever it goes without flaking off.

Conclusion

Is Electrolytic Tin Plate suitable for DRD processes? Absolutely. It remains the industry standard for a reason. Its unique combination of plasticity, natural lubricity, and safe food contact properties makes it hard to beat. By understanding the nuances of temper selection, anisotropy (earing), and surface finish, you can optimize your production line to run faster with less scrap. If you are ready to dial in your specs, let’s talk about getting you some samples to test on your line.

Footnotes

1. Overview of the two-piece food can manufacturing industry. ↩︎

2. Comparison of Electrolytic Tin Plate versus Tin-Free Steel. ↩︎

3. Definition of yield strength in material science. ↩︎

4. Explanation of the batch annealing heat treatment process. ↩︎

5. How directional properties in materials affect metal forming. ↩︎

6. Technical definition of the plastic strain ratio (r-value). ↩︎

7. Understanding the work hardening exponent in metallurgy. ↩︎

8. Properties and applications of Interstitial Free (IF) steels. ↩︎

9. Causes and prevention of galling in metal manufacturing. ↩︎

10. Chemical surface treatment to improve corrosion resistance. ↩︎