I know the specific panic that comes from seeing a quality report mention "swollen cans" or "internal rust." When you are dealing with high-heat sterilization, choosing the wrong tinplate specification does not just mean a few bad cans; it risks your entire production batch. Let me help you fix this risk permanently.

The optimal tin coating for retort processing typically requires a coating weight of 5.6/5.6 g/m² combined with 311 passivation. For acidic foods in plain cans, a heavier 11.2 g/m² K-Plate is essential, while lacquered cans rely on a robust epoxy-phenolic or BPA-NI system to withstand sterilization temperatures.

Let’s break down the technical nuances of coating weights, passivation, and lacquer systems so you can buy with absolute confidence and protect your brand reputation.

Does high-temperature sterilization require a thicker tin layer?

You might think that "thicker is always better" when it comes to safety, but over-specifying your tin weight kills your profit margins. I want to help you find that exact "sweet spot" where cost efficiency meets absolute food safety.

High-temperature sterilization generally demands a minimum tin coating of 2.8/2.8 g/m² for lacquered cans to ensure proper adhesion. However, plain cans relying on sacrificial protection need significantly thicker coatings, often exceeding 11.2 g/m², to maintain the continuity of the iron-tin alloy layer under thermal stress.

When we talk about retort processing 1—usually involving temperatures between 115°C and 130°C (240°F–265°F)—we are subjecting the metal to intense "thermal shock." In my experience at Huajiang, I have seen many buyers focus solely on the tin weight number without understanding the underlying mechanism.

The Role of the Alloy Layer

The most critical factor here is not just the free tin on top, but the Iron-Tin Alloy layer 2 (FeSn2) that sits between the steel base and the tin. During the retort process, the heat can cause the tin to reflow or shift. If you use a coating that is too thin (like 1.1 g/m²), the alloy layer may be discontinuous. Under high heat and pressure, these gaps become weak points where corrosion starts immediately.

K-Plate: The Acidic Solution

For acidic fruits or tomato products that are retorted in "plain" (unpainted) cans to preserve color and flavor, standard tinplate is not enough. You must use K-Plate 3. This is a specific grade of electrolytic tinplate with high corrosion resistance, characterized by a low Iron Solution Value (ISV). We control the steel chemistry to ensure the tin crystals form a dense, protective barrier. If you use standard plate for acidic retort foods, you will see "detinning" happen rapidly, leading to hydrogen swelling 4 (puffing) within months.

Recommendations for Coating Weights

I have compiled a guide based on what I supply to my biggest clients in Europe and South America. This helps visualize where you should be:

| Food Type | Retort Temperature | Recommended Tin Coating (Internal) | Why? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic Fruits (Plain) | < 100°C (Pasteurization) | 11.2 g/m² (D 100) | Tin acts as a sacrificial anode to protect steel. |

| Vegetables/Meats (Lacquered) | 115°C – 121°C | 5.6 g/m² (D 50) | Balanced protection; tin supports lacquer adhesion. |

| Pet Food (Lacquered) | 121°C – 130°C | 2.8 g/m² or 5.6 g/m² | Lacquer does the heavy lifting; tin prevents under-film corrosion. |

| Aggressive Pickles | Varies | 8.4 g/m² or higher | High salt and acid require extra insurance against pitting. |

You must remember that the retort environment creates a pressure difference. If the tin coating is too thin, the expansion and contraction can cause micro-fractures in the surface. Even if you cannot see them with the naked eye, these fractures are entry points for the liquid to attack the steel base. Therefore, while you can save money on the outside of the can with a lighter coating (differential coating 5), never skimp on the inside coating for retort goods.

Can I use a lower tin coating if I apply a double lacquer?

It is tempting to slash your tinplate costs by relying heavily on paint to do the job. I have seen many buyers try this strategy to improve their bottom line, but it requires precise calibration to avoid catastrophic failure.

You can reduce tin coating weights to 1.1/1.1 g/m² or 2.8/2.8 g/m² if a high-quality double lacquer system is applied. The organic coating becomes the primary barrier, but the underlying tin must still provide sufficient surface free energy to prevent lacquer delamination during the retort cooling cycle.

This is a strategy I often discuss with clients who are facing price pressure from steel markets. The short answer is yes, you can lower the tin weight, but the "system" becomes more complex. You are moving from a "sacrificial" protection model to a "barrier" protection model.

The Adhesion Challenge

When you reduce tin weight to 1.1 g/m² or 2.8 g/m², the risk is not that the tin will run out; the risk is that the lacquer will peel off. Tin provides a natural chemical affinity for many lacquers. When there is very little tin, the lacquer has to bond almost directly to the steel/alloy layer. During the retort process, the metal expands at a different rate than the organic lacquer coating.

If the adhesion is poor, you get lacquer delamination 6 (blistering). Once a blister forms, the food acids get trapped underneath, and the can rusts through from the inside in weeks.

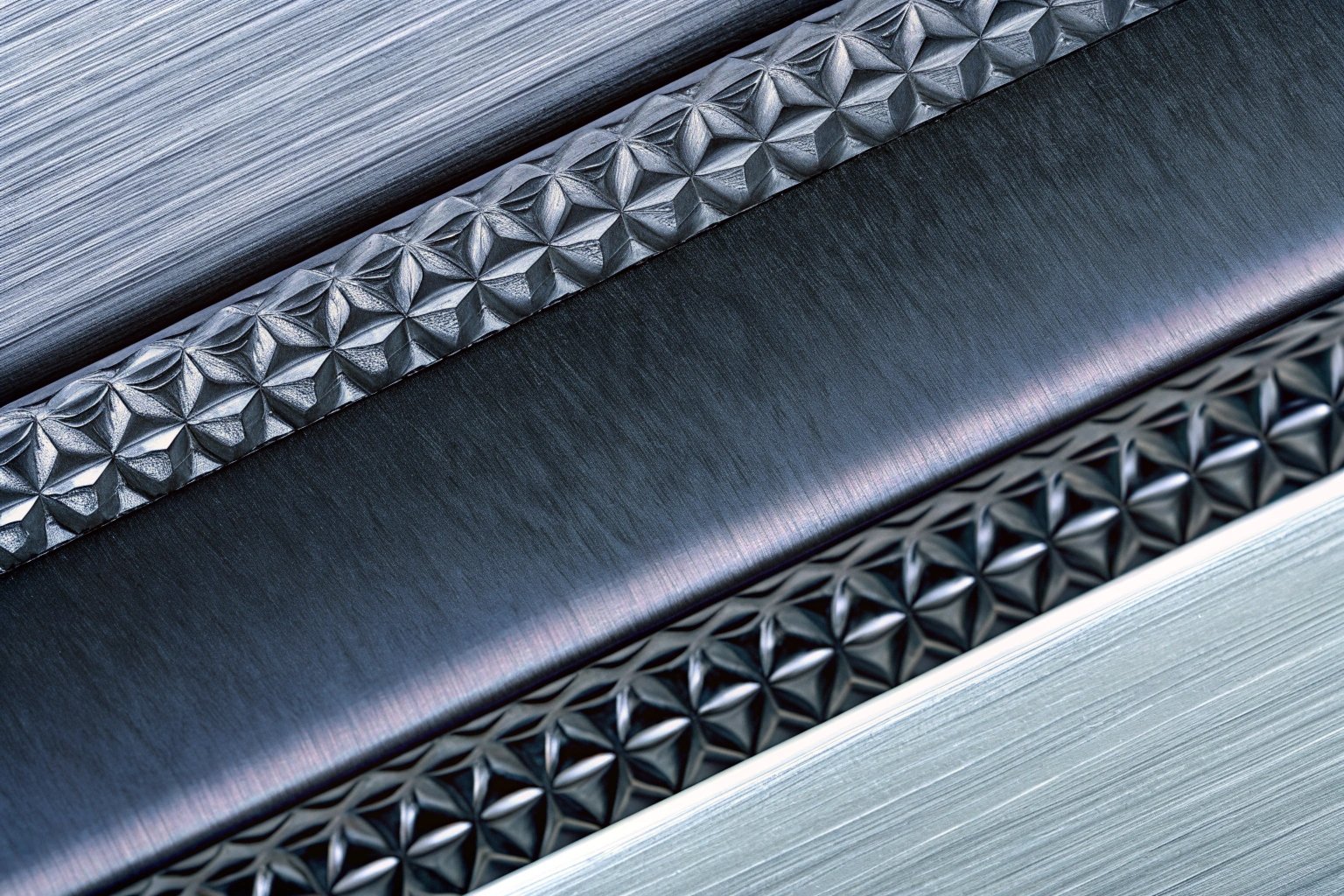

Surface Finish Matters

If you choose to go with lower tin and double lacquer, I strongly advise you to switch to a Stone Finish or Matte Finish rather than a Bright Finish.

- Bright Finish: Smooth and shiny. Harder for lacquer to "grip."

- Stone Finish: Rougher texture (Ra 0.25–0.60 µm). This acts like mechanical teeth, giving the lacquer something to hold onto during the thermal shock of sterilization.

Choosing the Right Lacquer

Not all paints are equal in a retort cooker. If you lower your tin weight, your lacquer selection must be flawless. Here is how I categorize them for my clients:

| Lacquer Type | Adhesion to Low Tin | Retort Performance | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy-Phenolic | Excellent | Superior | The "Gold Standard" for meats, fish, and corn. |

| Polyester (BPA-NI) | Moderate | Good | Required for EU markets; needs careful curing control. |

| Organosol | Good | Excellent (Flexible) | Best for easy-open ends (EOE) that need to bend without cracking. |

| Acrylic | Poor | Poor | Do not use for retort; it turns white (blushing) and peels. |

The "BPA-NI" Factor

I must warn you about the shift to BPA-NI 7 (Non-Intent) coatings. Polyester-based BPA-NI lacquers generally have lower adhesion than traditional epoxies. If you are shipping to Europe and require BPA-NI, you cannot risk dropping your tin weight too low. I usually recommend keeping the tin at minimum 2.8 g/m² for BPA-NI retort cans to provide that extra safety margin for adhesion.

How do I prevent sulfide blackening during the retort process?

Nothing ruins a brand reputation faster than a customer opening a premium can of corn or meat and seeing ugly black spots on the lid. I know you cannot afford that kind of consumer complaint, and the solution lies in the chemistry of the plate.

Sulfide blackening is best prevented using 311 Passivation (sodium dichromate), which creates a chromium oxide barrier. For high-protein foods like meats, this must be paired with a sulfur-resistant lacquer containing zinc oxide or aluminum pigment to trap sulfide ions before they react with the tin.

Sulfide staining 8 is the most common visual defect in retort canned foods, especially for "high sulfur" products like sweet corn, green peas, fish, and meats. It happens when sulfur amino acids in the food break down during the heat of sterilization. These sulfur ions attack the tin, forming Tin Sulfide (SnS), which looks purple or black. It is not toxic, but it looks terrible to the consumer.

The Power of Passivation

The first line of defense is the passivation 9 treatment applied at the steel mill.

- 311 Passivation: This is an electrochemical treatment in a sodium dichromate bath. It deposits a stable chromium oxide layer on the tin surface. This layer is very effective at resisting surface reactions. For any retort food, I basically insist my clients use 311.

- 300 Passivation: This is a simple chemical dip. It is too weak for retort processing. The heat will break down the protection immediately.

The Trap of "Chromium-Free"

We are seeing more demand for Chromium-Free Passivation Alternatives (CFPA) due to environmental regulations. However, you must be careful. Early generations of CFPA performed poorly in retort conditions, turning yellow or allowing staining. If you must go chromium-free, ensure your supplier uses a validated system (like the latest generation EZP) that has passed the "pressure cooker test."

Specialized Lacquer Additives

Sometimes, passivation alone is not enough, especially for luncheon meat or tuna. In these cases, the lacquer acts as a chemical sponge.

- Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Additives: We add white zinc oxide powder to the lacquer. The sulfur reacts with the zinc to form Zinc Sulfide (which is white and invisible) instead of reacting with the tin (which turns black). This keeps the can looking clean.

- Aluminum Pigment: For some meats, we use a silver-colored lacquer filled with aluminum powder. This creates a physical barrier so dense that the sulfur ions physically cannot reach the tinplate surface.

Diagnostic Checklist

If you are seeing blackening now, ask these three questions:

- Is the passivation confirmed as 311 (electrochemical) or just 300?

- Is the lacquer explicitly formulated with sulfur-absorbing agents?

- Is the coating weight uniform? Sometimes "thin spots" in the tin coating (below 1.1 g/m²) react faster.

What are the specific specifications for tuna or meat cans?

Tuna and luncheon meat are high-stakes products because of their oil content, salt levels, and long shelf life. I want to share the exact specifications that global giants use so you do not have to guess or experiment with your budget.

For tuna and meat cans, the industry standard specification uses 5.6/5.6 g/m² tinplate with 311 passivation and a DR-8 temper for strength. The internal coating typically requires an aluminized epoxy-phenolic lacquer to mask sulfide staining and withstand the aggressive protein-sulfur reaction during the 90-minute retort cycle.

When we supply material for tuna or meat packing, we treat it differently than fruit or vegetable cans. These foods are chemically aggressive in a unique way. They contain fats, oils, and proteins that can penetrate inferior coatings during the high-heat cycle.

The "Tuna Spec" Deep Dive

Tuna is unique because it is often packed in oil or brine. Oil has a nasty habit of softening organic coatings at high temperatures.

- Base Steel: We typically use Double Reduced 10 (DR-8) steel. Why? Because tuna cans are usually shallow and drawn (2-piece DRD cans). The steel needs to be stiff and strong (around 550 MPa yield strength) to hold its shape during the vacuum sealing and retorting, yet thin enough (0.17mm – 0.20mm) to be cost-effective.

- Tin Coating: We recommend 5.6/5.6 g/m². While some try to use 2.8, the salt content in tuna brine is corrosive. The 5.6 weight gives you that extra shelf-life security (2-3 years) that supermarkets demand.

- Lacquer: This is non-negotiable. You need an Aluminized Epoxy-Phenolic. The aluminum pigment hides any potential sulfur stains (tuna is high in sulfur), and the epoxy is resistant to the fish oil.

The "Luncheon Meat Spec" Deep Dive

Meat cans (like spam or corned beef) are often square or rectangular. This shape introduces stress on the corners of the can.

- Release Agents: Meat tends to stick to the can. If the consumer cannot slide the meat out smoothly, they blame the brand. Therefore, the internal lacquer for meat cans often includes a "Meat Release Agent" (internal wax/slip additive).

- Passivation: As mentioned earlier, 311 Passivation is critical here to stop the "purple sulfide bloom" on the lid and body.

Comparison of Standard Specs

Here is a quick reference for the two most common retort protein applications:

| Feature | Tuna (2-Piece DRD) | Luncheon Meat (3-Piece Rectangular) |

|---|---|---|

| Steel Temper | DR-8 (Stiff, high strength) | T3 or T4 (Softer, needs to form corners) |

| Thickness | 0.17mm – 0.21mm | 0.22mm – 0.26mm |

| Tin Coating | 5.6 g/m² (E 5.6/5.6) | 5.6 g/m² or 8.4 g/m² |

| Internal Lacquer | Aluminized Epoxy-Phenolic | Phenolic with Meat Release Agent |

| External Lacquer | Gold/Clear Epoxy | White/Print |

| Key Risk | Oil softening the lacquer | Sulfide blackening & Corner cracking |

If you are buying for these sectors, do not accept generic "food grade" tinplate. You must specify the lacquer performance regarding sulfur resistance and oil resistance. A generic polyester paint will soften and peel in a tuna can retort process, ruining the entire shipment.

Conclusion

To guarantee safety and efficiency in retort processing, stick to a 5.6/5.6 g/m² tin coating with 311 passivation, and always match your internal lacquer to the specific acidity and sulfur content of your food.

Footnotes

1. Overview of thermal sterilization techniques for commercial food safety. ↩︎

2. Technical details on the intermetallic layer essential for adhesion. ↩︎

3. Specifications for tinplate designed with high corrosion resistance. ↩︎

4. Causes and prevention of gas buildup in canned foods. ↩︎

5. Benefits of using different coating weights on can sides. ↩︎

6. Analysis of coating adhesion failures under thermal stress. ↩︎

7. Regulatory updates and safety data on non-BPA coatings. ↩︎

8. Identification and prevention of discoloration in protein foods. ↩︎

9. Chemical process protecting metals from surface corrosion. ↩︎

10. Properties of stiffer, thinner steel for cost-effective canning. ↩︎